What Is Psychological Health?

-

LO 1 Define each of the four components of psychological health, and identify the basic traits shared by psychologically healthy people.

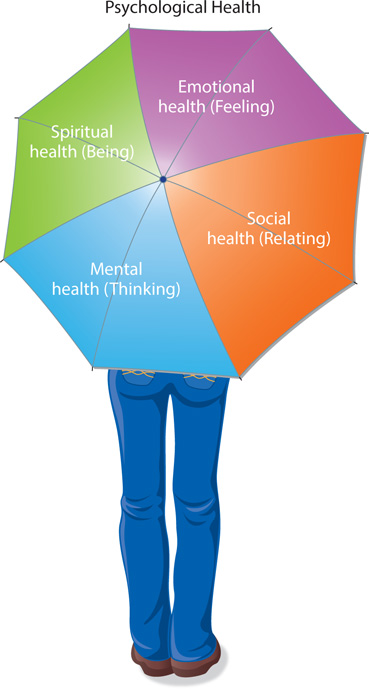

Psychological health is the sum of how we think, feel, relate, and exist in our day-to-day lives. Our thoughts, perceptions, emotions, motivations, interpersonal relationships, and behaviors are a product of our experiences and the skills we have developed to meet life’s challenges. Psychological health includes mental, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Psychological Health

Psychological health is a complex interaction of the mental, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions of health. Possessing strength and resiliency in these dimensions can maintain your overall well-being and help you weather the storms of life.

Most experts identify several basic elements psychologically healthy people regularly display:

-

They feel good about themselves. They are not typically overwhelmed by fear, love, anger, jealousy, guilt, or worry. They know who they are, have a realistic sense of their capabilities, and respect themselves even though they realize they aren’t perfect.

-

They feel comfortable with other people, respect others, and have compassion. They enjoy satisfying and lasting personal relationships and do not take advantage of others or allow others to take advantage of them. They accept that there are others whose needs are greater than their own and take responsibility for fellow human beings. They can give love, consider others’ interests, take time to help others, and respect personal differences.

-

They are “self-compassionate.” Kind and understanding of their own imperfections and weaknesses, they acknowledge their “humanness.” They are mindful of the problems in life and work to be the best that they can be, given their limitations and things they can’t control. They are not self-absorbed, narcissistic, or overly critical of themselves.1

-

They control tension and anxiety. They recognize the underlying causes and symptoms of stress and anxiety in their lives and consciously avoid irrational thoughts, hostility, excessive excuse making, and blaming others for their problems. They use resources and learn skills to control reactions to stressful situations.

-

They meet the demands of life. They try to solve problems as they arise, accept responsibility, and plan ahead. They set realistic goals, think for themselves, and make independent decisions. Acknowledging that change is inevitable, they welcome new experiences.

-

They curb hate and guilt. They acknowledge and combat tendencies to respond with anger, thoughtlessness, selfishness, vengefulness, or feelings of inadequacy. They do not try to knock others aside to get ahead, but rather reach out to help others.

-

They maintain a positive outlook. They approach each day with a presumption that things will go well. They look to the future with enthusiasm rather than dread. Having fun and making time for themselves are integral parts of their lives.

-

They value diversity. They do not feel threatened by those of a different gender, religion, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, age, or political party. They are nonjudgmental and do not force their beliefs and values on others.

-

They appreciate and respect the world around them. They take time to enjoy their surroundings, are conscious of their place in the universe, and act responsibly to preserve their environment.

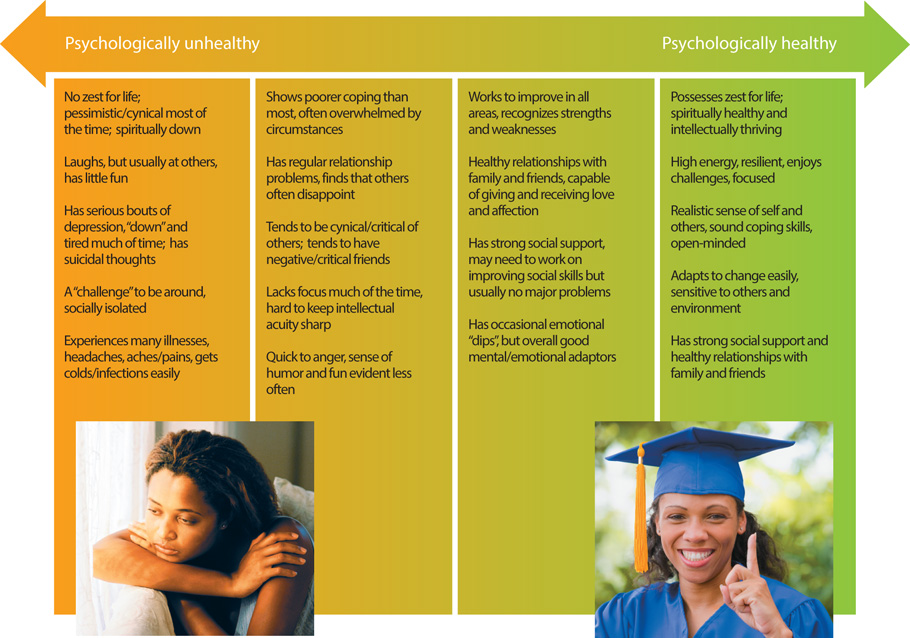

In sum, psychologically healthy people possess emotional, mental, social, and spiritual resiliency. Resilient individuals have the ability to overcome challenges from minor disappointments to major tragedies and the typical life obstacles we often face. They usually respond to challenges and frustrations in appropriate ways, despite occasional slips (see Figure 2.2). When they do slip, they recognize it, are kind to themselves rather than engaging in endless self-recrimination, and take action to rectify the situation.

Figure 2.2 Characteristics of Psychologically Healthy and Unhealthy People

Where do you fall on this continuum?

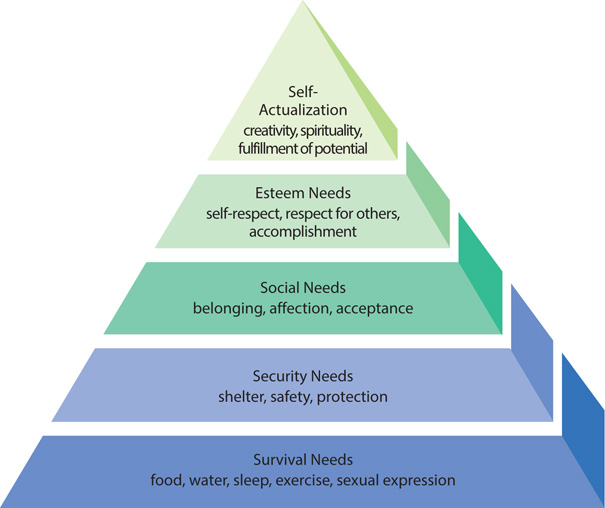

Psychologists have long argued that before we can achieve any of the above characteristics of psychological health, we must meet certain basic human needs. In the 1960s, human theorist Abraham Maslow developed a hierarchy of needs to describe this idea (Figure 2.3): At the bottom of his hierarchy are basic survival needs, such as food, sleep, and water; at the next level are security needs, such as shelter and safety; at the third level—social needs—is a sense of belonging and affection; at the fourth level are esteem needs, self-respect and respect for others; and at the top are needs for self-actualization and self-transcendence.

Figure 2.3 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Source: From A. H. Maslow, Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed., eds. R. D. Frager and J. Fadiman (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 1987). Reprinted with permission.

Watch

Video Tutor: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

According to Maslow’s theory, a person’s needs must be met at each of these levels before he or she can be truly healthy. Failure to meet needs at a lower level will interfere with a person’s ability to address higher-level needs. For example, someone who is homeless or worried about threats from violence will be unable to focus on fulfilling social, esteem, or actualization needs.2

Mental Health

The term mental health is used to describe the “thinking” or “rational” dimension of our health. A mentally healthy person perceives life in realistic ways, can adapt to change, can develop rational strategies to solve problems, and can carry out personal and professional responsibilities. In addition, a mentally healthy person has the intellectual ability to learn and use information effectively and strive for continued growth. This is often referred to as intellectual health, a subset of mental health.3

Emotional Health

The term emotional health refers to the feeling, or subjective, side of psychological health. Emotions are intensified feelings or complex patterns of feelings that we experience on a regular basis, including love, hate, frustration, anxiety, and joy, just to name a few. Typically, emotions are described as the interplay of four components: physiological arousal, feelings, cognitive (thought) processes, and behavioral reactions. As rational beings, we are responsible for evaluating our individual emotional responses, their causes, and the appropriateness of our actions.

Emotionally healthy people usually respond appropriately to upsetting events. Rather than reacting in an extreme fashion or behaving inconsistently or offensively, they can express their feelings, communicate with others, and show emotions in appropriate ways. In contrast, emotionally unhealthy people are much more likely to let their feelings overpower them. They may be highly volatile and prone to unpredictable emotional responses, which may be followed by inappropriate communication or actions.

Emotional health also affects social and intellectual health. People who feel hostile, withdrawn, or moody may become socially isolated. Because they are not much fun to be around, people may avoid them at the very time they are most in need of emotional support. For students, a more immediate concern is the impact of emotional upset on academic performance. Have you ever tried to study for an exam after a fight with a friend or family member? Emotional turmoil can seriously affect your ability to think, reason, and act rationally.

Social Health

Social health includes your interactions with others on an individual and group basis, your ability to use social resources and support in times of need, and your ability to adapt to a variety of social situations. Socially healthy individuals enjoy a wide range of interactions with family, friends, and acquaintances and are able to have healthy interactions with an intimate partner. Typically, socially healthy individuals can listen, express themselves, form healthy attachments, act in socially acceptable and responsible ways, and find the best fit for themselves in society. Numerous studies have documented the importance of positive relationships with family members, friends, and significant others to overall well-being and longevity.4

The Family

Families have a significant influence on psychological development. Healthy families model and help develop the cognitive and social skills necessary to solve problems, express emotions in socially acceptable ways, manage stress, and develop a sense of self-worth and purpose. Children raised in healthy, nurturing homes are more likely to become well-adjusted, productive adults. In adulthood, family support is one of the best predictors of health and happiness.5 Children brought up in dysfunctional families—in which there is violence; distrust; anger; dietary deprivation; drug abuse; significant parental discord; or sexual, physical, or emotional abuse—may have a harder time adapting to life and may have an increased risk of psychological problems.6 In dysfunctional families, love, security, and unconditional trust may be so lacking that children become psychologically damaged. Yet not all people raised in dysfunctional families become psychologically unhealthy, and not all people from healthy environments become well adjusted. The difference may lie in their support system, community, self-esteem, and personality.

Social Supports

Our initial social support may be provided by family members, but as we grow and develop, the support of peers and friends becomes more and more important. We rely on friends to help us figure out who we are and what we want to do with our lives. We often bounce ideas off friends to see if they think we are being logical, smart, or fair. Research shows that college students with adequate social support have improved overall well-being, including higher GPAs, higher perceived ability in math and science courses, less peer pressure for binge drinking, lower rates of suicide, and higher overall life satisfaction.7 Relationships in life provide the social capital that helps us maintain psychological health in the face of life’s challenges.

Your family members play an important role in your psychological health. As you were growing up, they modeled behaviors and skills that helped you develop cognitively and socially. Their love and support can give you a sense of self-worth and encourage you to treat others with compassion and care.

Although we often hear the term social support used, this concept is actually more complex than many people realize. In general, it refers to the people and services with whom we interact and share social connections. These ties can provide tangible support, such as babysitting services or money to help pay the bills, or intangible support, such as encouraging you to share your concerns. Sometimes, support can just be the knowledge that someone would be there for you in a crisis. Research shows that college students with adequate social support have improved overall well-being, including higher GPAs, higher perceived ability in math and science courses, less stress and depression, less peer pressure for binge drinking, lower rates of suicide, and higher overall life satisfaction.8 (Look for more information about interpersonal relationships in Chapter 8.)

Community

The communities we live in can provide social support and have a positive impact on our psychological health through collective actions. For example, neighbors may join together to get rid of trash on the street, participate in a neighborhood watch to keep children and homes safe, help each other with home repairs, or organize community social events. Religious institutions, schools, clinics, and local businesses can also engage in efforts that demonstrate support and caring for community members. Likewise, you are a part of a campus community. That community can support and care for your psychological health by creating a safe environment to explore and develop your mental, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions.

Loneliness

What makes us happiest in life? Some people may point to fabulous fame and fortune. But happiness is most closely connected to having friends and family. Even though our need to connect is innate, some of us always go home alone. You could have people around you throughout the day or even be in a lifelong marriage and still experience a deep, pervasive loneliness. Loneliness is not the same as being alone. Loneliness is a feeling of emptiness or hollowness inside of you, causing people to feel alone and unwanted.

There are several possible contributors to increased reports of loneliness in modern society. Most commonly, divorce and death; aging/living longer and losing most of the people who have ever known us; increased use of social media, where we connect with people but may not have as many close social relationships; access to transportation; community structure and walking paths; a more mobile workforce, where people may telecommute or change jobs and locations frequently; and a host of other factors have been discussed as reasons for social isolation.9 A recent study of twins raised apart and together provides preliminary evidence that genetics may play a key role in risk for loneliness. More research is necessary to determine the nature and extent of this relationship.10

Loneliness has a wide range of negative effects on both physical and mental health. Some of the health risks of loneliness include depression and suicide; increased stress levels; antisocial behavior; and alcohol and drug abuse.11

Finding ways to change feelings of loneliness is key. Recognize the feelings of loneliness and find ways to express these feelings through journaling, writing, or reaching out to a friend or counselor on campus. It is not unusual for other students on campus to experience loneliness. In fact, approximately 59 percent of college students reported feeling lonely in the past year.12 Becoming engaged in a campus activity or club that you enjoy provides an opportunity to look forward to something and to meet with others that have similar interests.

Spiritual Health

It is possible to be mentally, emotionally, and socially healthy and still not achieve optimal psychological well-being. For many people, the difficult-to-describe element that gives life purpose is the spiritual dimension.

The term spirituality is broader in meaning than religion and is defined as an individual’s sense of purpose and meaning in life; it involves a sense of peace and connection to others.13 Spirituality may be practiced in many ways, including through religion; however, religion does not have to be part of a spiritual person’s life. Spiritual health refers to the sense of belonging to something greater than the purely physical or personal dimensions of existence. For some, this unifying force is nature; for others, it is a feeling of connection to other people; for still others, the unifying force is a god or other higher power. (Focus On: Cultivating Your Spiritual Health, explores spiritual health and the role spirituality plays in your overall psychological health in more detail.)