1.1 The First Americans

-

Who were the first Americans, and how did they get to America?

Follow the Water

Many thousands of years ago, the first humans entered what their distant descendants would call the New World. The world was indeed new to them, but they had no idea what it contained. Almost certainly they came from Asia, by all odds across a wide plain that then connected Siberia to Alaska. The earth was in a cold spell—an ice age—and glaciers held much of the water that later would form the Bering Sea and Bering Strait and separate Asia from America.

The first arrivals didn’t think of themselves as explorers; rather, they were hunters in pursuit of game across the windy tundra. They didn’t travel very far into America; at the time, with the continents joined, it was unclear where Asia ended and America began. They moved slowly and cautiously, perhaps only miles per generation.

But gradually, their descendants spread south throughout North America. And who wouldn’t have wanted to continue south to find a climate and country more hospitable than the frozen lands of the north? Their numbers increased, and they adapted to different environmental niches. Some remained chiefly hunters; others complemented wild game with naturally occurring fruits and vegetables. Still others eventually cultivated plants, including corn, beans, and squashes.

As their numbers grew they spread still further. They pushed to the east until they hit the Atlantic Ocean; they moved south to where North America funneled into Central America and then the land broadened again, into South America.

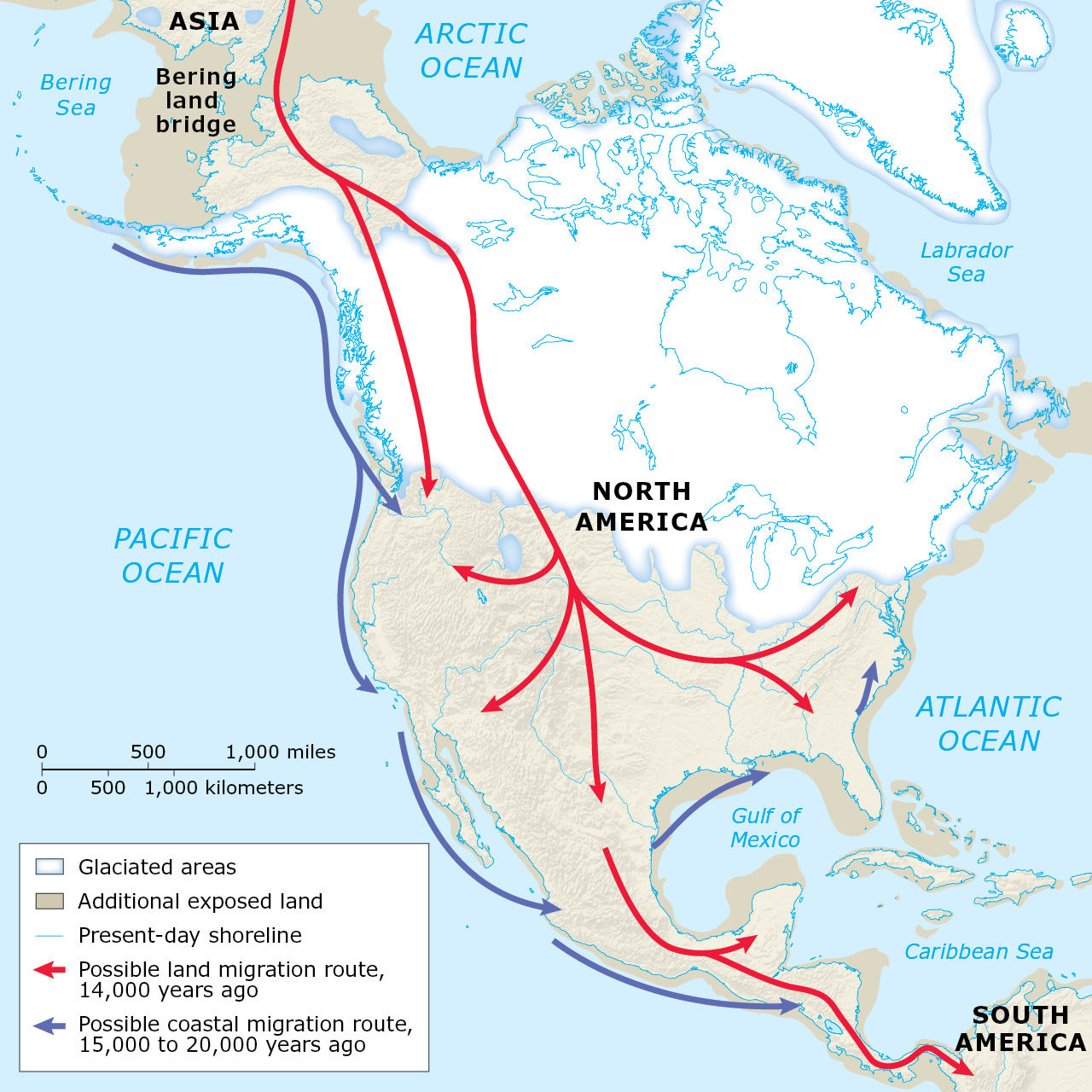

Map 1.1

Migration Routes into the Americas

Wandering hunters from Asia crossed the Bering land bridge and spread south throughout North America. Some may have followed the coast. The migration took thousands of years, and its source was cut off when the ocean level rose.

How many they became was a question they didn’t think to ask themselves, since almost none of them conceived of themselves as Americans, as part of any group larger than their bands and their tribes. Later students of the subject—modern anthropologists—would guess at a number between 10 million and 100 million.

In most places, they lived far apart, touching lightly on the land. But in a few places, their agriculture supported a density of population as great as that which existed in the Old World from which their ancestors had come. They developed cities and governments and religions and cultures—all the facets of civilization found in the Old World.

The pioneers who first crossed over to America were almost certainly hungry. Hunger was the normal condition of life for most prehistoric people for much of the time. And these hunters were more likely to be hungry than most, for they were venturing into inhospitable territory on the trail of dangerous game. Nothing but hunger would have caused them to think that taking on woolly mammoths or mastodons with stone-tipped wooden spears was a good idea. Quite possibly, they weren’t very successful hunters. As a general rule (in later eras, and probably then) successful individuals didn’t risk their lives on the frontiers of their communities’ existence. The successful ones stayed home, comparatively fat and happy.

AMERICAN MASTODON Mastodons roamed North America when the first arrivals from Asia appeared. The newcomers might have helped drive the big animals to extinction.

Source: Arthur Dorety/Stocktrek Images/Alloy/Corbis

The newcomers ventured forward cautiously onto the barren plain that stretched east from Siberia. They had no way of knowing that this plain hadn’t always existed and wouldn’t always exist. They had no way to tell that the glaciers that locked up a large portion of the earth’s water, covering millions of square miles and to depths of thousands of feet, weren’t a permanent feature of the landscape. They couldn’t have had any idea that one day the sea would close behind where they now ventured, cutting their descendants off from the land and communities they now left behind.

The newcomers moved no faster than they had to. When the game held out, they stayed in place, perhaps for decades or centuries. But over hundreds and then thousands of years, they gradually spread throughout the Americas. As they did, they adjusted to new climates and new environments. The overall climate of the earth grew warmer, for reasons scientists still don’t entirely understand; the glaciers receded and the oceans rose. The new climate helped shape the terrain and vegetation that characterize the Americas to the present.

Those that stayed in North America found a distinctive terrain and vegetation. In the center of the continent, reaching south from the edge of the Arctic forest, was a swath of open plains, later called the Great Plains, that stretched to the Gulf of Mexico. To the east of the plains was a vast forest that extended almost unbroken to the Atlantic Ocean. In the middle of this forest was a chain of mountains that ran roughly parallel to the Atlantic shore. These mountains, which would be called the Appalachians, were not especially high, but they were rugged enough that animals and humans avoided crossing them when they didn’t have to. And when they did have to, they sought low-lying gaps and passes.

To the west of the great central plain were more mountains. These, the Rockies, were much higher than the eastern mountains; some of their peaks retained snow year-round. Oddly, they could be easier to cross than the eastern mountains, at least in those places where the plain led to wide valleys reaching far into the mountains.

West and south of the mountains was a fearsome desert. Summers were scorching, winters could be bone-chilling, and rain rarely fell. Game animals shunned the desert; consequently, so did humans.

In the middle of the continent ran a great river. One tributary drained much of the eastern half of the continent; another drained a large part of the west. These three rivers—the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the Missouri—would shape travel routes and settlement patterns for centuries, as humans learned to build boats that they paddled or otherwise propelled up and down the streams.