Chapter 1 Old Worlds and New, 40,000 bce to 1400 ce

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter Outline

1.1 The First Americans

-

Who were the first Americans, and how did they get to America?

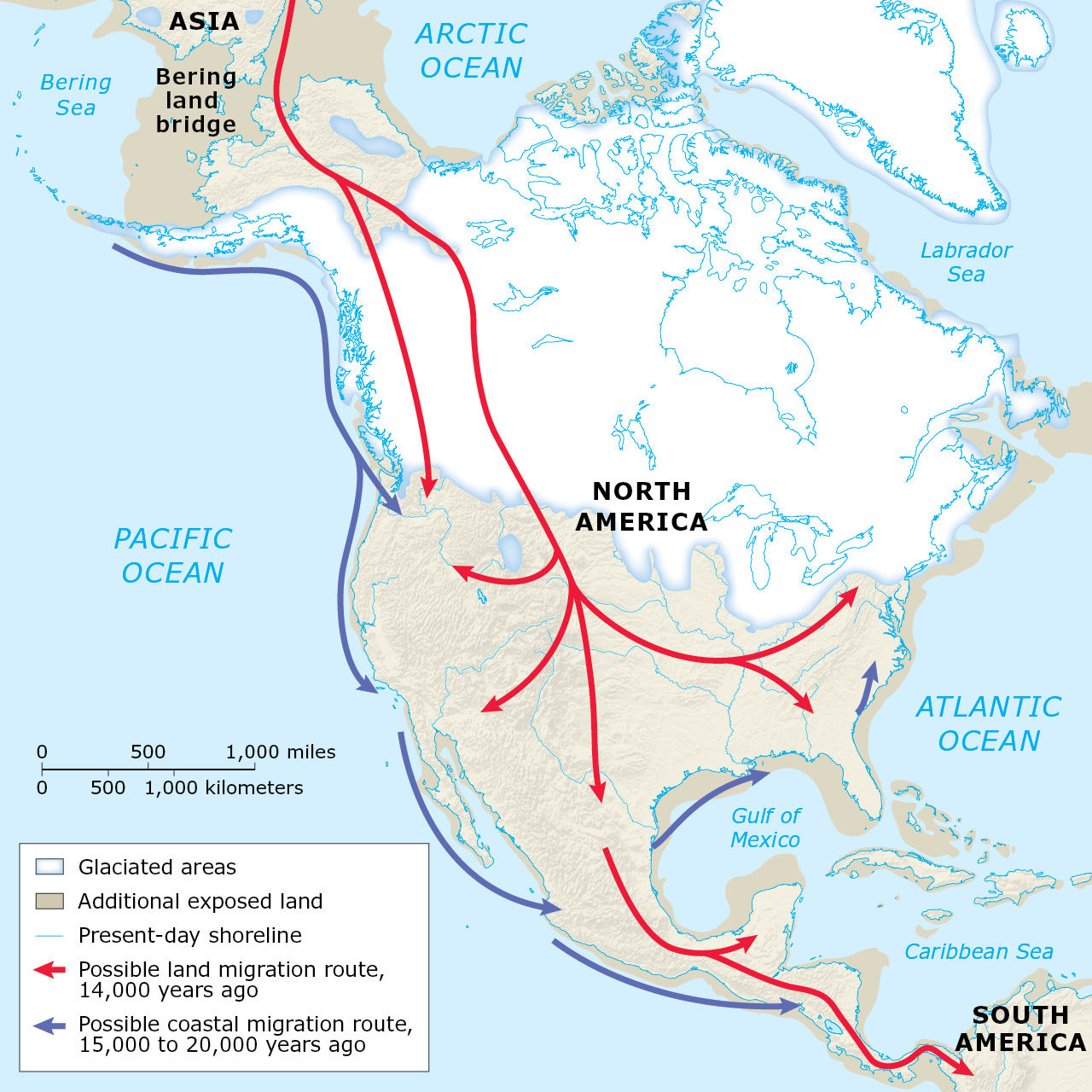

Follow the Water

Many thousands of years ago, the first humans entered what their distant descendants would call the New World. The world was indeed new to them, but they had no idea what it contained. Almost certainly they came from Asia, by all odds across a wide plain that then connected Siberia to Alaska. The earth was in a cold spell—an ice age—and glaciers held much of the water that later would form the Bering Sea and Bering Strait and separate Asia from America.

The first arrivals didn’t think of themselves as explorers; rather, they were hunters in pursuit of game across the windy tundra. They didn’t travel very far into America; at the time, with the continents joined, it was unclear where Asia ended and America began. They moved slowly and cautiously, perhaps only miles per generation.

But gradually, their descendants spread south throughout North America. And who wouldn’t have wanted to continue south to find a climate and country more hospitable than the frozen lands of the north? Their numbers increased, and they adapted to different environmental niches. Some remained chiefly hunters; others complemented wild game with naturally occurring fruits and vegetables. Still others eventually cultivated plants, including corn, beans, and squashes.

As their numbers grew they spread still further. They pushed to the east until they hit the Atlantic Ocean; they moved south to where North America funneled into Central America and then the land broadened again, into South America.

Map 1.1

Migration Routes into the Americas

Wandering hunters from Asia crossed the Bering land bridge and spread south throughout North America. Some may have followed the coast. The migration took thousands of years, and its source was cut off when the ocean level rose.

How many they became was a question they didn’t think to ask themselves, since almost none of them conceived of themselves as Americans, as part of any group larger than their bands and their tribes. Later students of the subject—modern anthropologists—would guess at a number between 10 million and 100 million.

In most places, they lived far apart, touching lightly on the land. But in a few places, their agriculture supported a density of population as great as that which existed in the Old World from which their ancestors had come. They developed cities and governments and religions and cultures—all the facets of civilization found in the Old World.

The pioneers who first crossed over to America were almost certainly hungry. Hunger was the normal condition of life for most prehistoric people for much of the time. And these hunters were more likely to be hungry than most, for they were venturing into inhospitable territory on the trail of dangerous game. Nothing but hunger would have caused them to think that taking on woolly mammoths or mastodons with stone-tipped wooden spears was a good idea. Quite possibly, they weren’t very successful hunters. As a general rule (in later eras, and probably then) successful individuals didn’t risk their lives on the frontiers of their communities’ existence. The successful ones stayed home, comparatively fat and happy.

AMERICAN MASTODON Mastodons roamed North America when the first arrivals from Asia appeared. The newcomers might have helped drive the big animals to extinction.

Source: Arthur Dorety/Stocktrek Images/Alloy/Corbis

The newcomers ventured forward cautiously onto the barren plain that stretched east from Siberia. They had no way of knowing that this plain hadn’t always existed and wouldn’t always exist. They had no way to tell that the glaciers that locked up a large portion of the earth’s water, covering millions of square miles and to depths of thousands of feet, weren’t a permanent feature of the landscape. They couldn’t have had any idea that one day the sea would close behind where they now ventured, cutting their descendants off from the land and communities they now left behind.

The newcomers moved no faster than they had to. When the game held out, they stayed in place, perhaps for decades or centuries. But over hundreds and then thousands of years, they gradually spread throughout the Americas. As they did, they adjusted to new climates and new environments. The overall climate of the earth grew warmer, for reasons scientists still don’t entirely understand; the glaciers receded and the oceans rose. The new climate helped shape the terrain and vegetation that characterize the Americas to the present.

Those that stayed in North America found a distinctive terrain and vegetation. In the center of the continent, reaching south from the edge of the Arctic forest, was a swath of open plains, later called the Great Plains, that stretched to the Gulf of Mexico. To the east of the plains was a vast forest that extended almost unbroken to the Atlantic Ocean. In the middle of this forest was a chain of mountains that ran roughly parallel to the Atlantic shore. These mountains, which would be called the Appalachians, were not especially high, but they were rugged enough that animals and humans avoided crossing them when they didn’t have to. And when they did have to, they sought low-lying gaps and passes.

To the west of the great central plain were more mountains. These, the Rockies, were much higher than the eastern mountains; some of their peaks retained snow year-round. Oddly, they could be easier to cross than the eastern mountains, at least in those places where the plain led to wide valleys reaching far into the mountains.

West and south of the mountains was a fearsome desert. Summers were scorching, winters could be bone-chilling, and rain rarely fell. Game animals shunned the desert; consequently, so did humans.

In the middle of the continent ran a great river. One tributary drained much of the eastern half of the continent; another drained a large part of the west. These three rivers—the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the Missouri—would shape travel routes and settlement patterns for centuries, as humans learned to build boats that they paddled or otherwise propelled up and down the streams.

1.2 Early Civilizations

-

What were the three main civilizations in early America?

Wheat, Rice, Corn: The Stuff of Civilization

The discovery of how to cultivate plants and the changes that resulted from this discovery constituted the Agricultural Revolution, which happened at least twice: once in Asia and once in the Americas. In both places, it transformed the way large numbers of people lived. Agriculture tied people to particular pieces of land, which became valuable enough to fight over. It allowed populations to grow far beyond the numbers that could be sustained by hunting and gathering alone. Cities emerged, and with cities came governments and what later generations would call civilizations (employing the Latin root for city). In some cases, the cities and civilizations expanded to become empires.

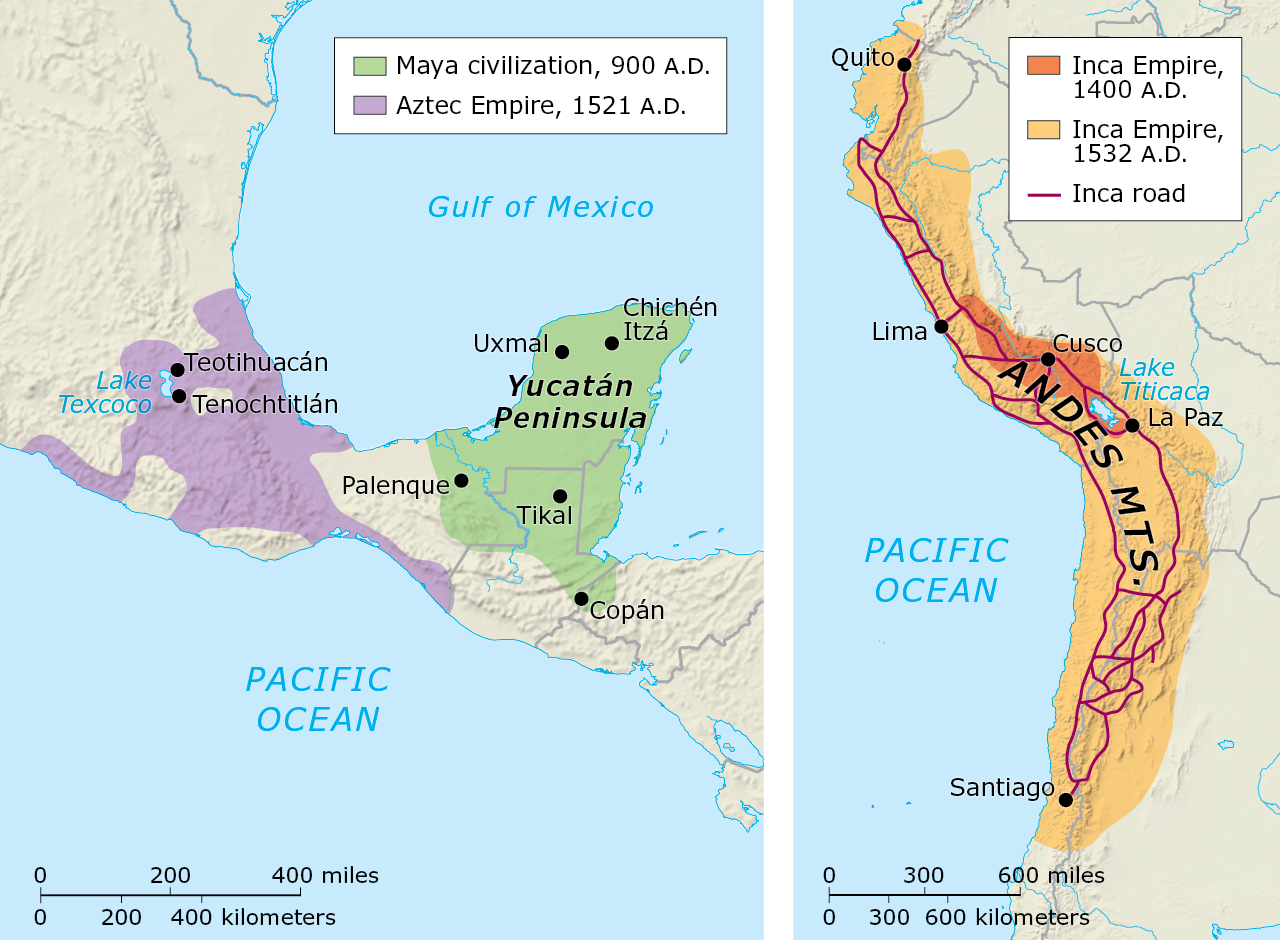

Map 1.2

Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations

Advanced civilizations developed in Central and South America. The Aztecs occupied the highlands of modern central Mexico. The Maya emerged in the lowlands of the Yucatán Peninsula. The Inca empire ran along the Andes Mountains.

In the Americas, there emerged three great civilizations. The earliest arose in the tropical forest of Central America. Starting some four thousand years ago, the Maya built broad cities of stone, remnants of which still stand today. Religion played a central role in Maya life; the largest structures in Maya cities were temples. The Maya developed sophisticated calendars and numbering systems; they understood the motion of the stars and planets as well as any people on earth. The Maya civilization gradually declined, for reasons unclear to modern anthropologists and historians but possibly related to changing climate. The Maya people didn’t vanish; they form a substantial portion of the modern population of Central America.

MAYA PYRAMID, CHICHÉN ITZÁ, MEXICO The Maya built great stone cities like this one at Chichén Itzá.

Source: Christian Delbert/Shutterstock

North of the Maya, centered in the high valley of what would become central Mexico, a second civilization emerged. The Aztecs were the most assertive of the peoples of the region; in time, they came to dominate and subjugate their neighbors and construct an empire. The Aztecs built a great city, Tenochtitlán, on an island in the middle of a lake in their valley. This city—the predecessor of Mexico City—was their stronghold and their religious center. They made sacrifices to their gods; among the sacrifices were humans, which their gods were thought to value most highly. The Aztec empire persisted into the modern period; Spanish explorers encountered the Aztecs in the early sixteenth century.

AZTEC PYRAMIDS, TENOCHTITLÁN, MEXICO The Pyramids of the Sun and Moon played a crucial role in the religious and cultural life of the Aztecs of central Mexico.

Source: Anna Omelchenko/Shutterstock

Far to the south, in the Andes Mountains of South America, the Incas created a third civilization. The Incas combined certain traits of the Maya and the Aztecs, being at once a highland people and a people of the forest. They conquered their neighbors and constructed a large empire, stretching two thousand miles from north to south. To knit their far-flung domain together, the Incas built an elaborate network of all-weather roads. They invented a system of record-keeping that involved complicated schemes of knot-tying. These quipu, as the knot arrangements were called, might have doubled as a kind of writing.

MACHU PICCHU, CUSCO, PERU The Inca city of Machu Picchu, high in the Andes, was lost to the outside world for centuries after the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Source: Amy Nichole Harris/Shutterstock

The civilizations of the Maya, the Aztecs, and the Incas revealed many of the same properties and tendencies of civilizations elsewhere. Societies were stratified into elites, who held power and wealth, and lower classes, who did most of the work. Governments made and enforced laws; they established alliances with some neighbors and waged war against others. Religion supported government and vice versa. The power of the governments waxed and waned, depending on the wisdom, talent, and ruthlessness of the rulers and the patience and ingenuity of the ruled.

1.3 The Indians of North America

-

What were the principal cultures of the Indians of North America?

The Potlach: Conspicuous Consumption among Northwest Indians

North of Mexico, in the region that would become the United States, nothing quite like the Maya, Aztec, or Inca civilizations emerged. Agriculture never developed as fully as farther south, and consequently the cities on which the civilizations depended never took root.

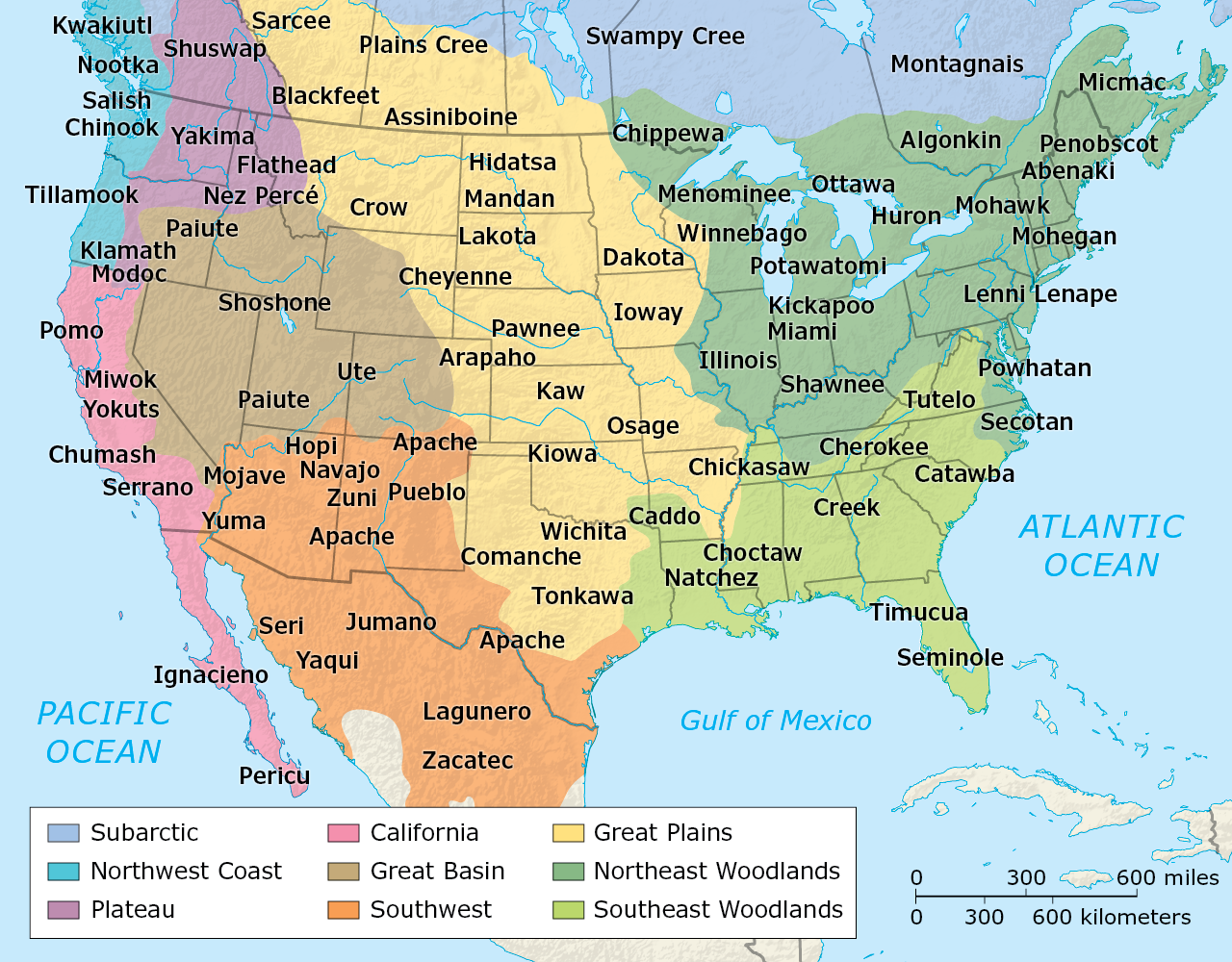

Map 1.3

Locations of North American Indian Cultures

The region that would become the United States was home to many Native American tribes and cultures. These included the Woodland peoples of the East, the Plains tribes of the center of the continent, and the distinctive cultures of the Southwestern desert and the Northwest coast.

Yet the peoples of North America developed distinctive cultures nonetheless. The Indians (to use the name the Spanish mistakenly applied to the indigenous peoples of the Americas) of the great central plains region were largely nomadic, hunting herds of bison, or buffalo, that migrated with the seasons. The Plains Indians originally tracked the buffalo on foot and forced or tricked them into going over cliffs. The fall would break the buffalos’ legs and render them easy prey to the hunters’ spears and arrows. Later the Plains tribes acquired horses from the Spanish and learned to hunt buffalo from horseback. The Plains Indians lived in tepees and accumulated no more material goods than they could easily transport. The lands they called their own were hunting grounds, which they defended against interlopers and expanded when necessity or opportunity arose. They regularly traded with their neighbors and sometimes fought with them over access to land, over women, and over material goods that weren’t too heavy or bulky to carry. Later, when horses expanded their range, they fought over horses.

PLAINS INDIAN TEPEE The tepee, light and portable, demonstrated the ability of the Plains Indians to make the most of their nomadic life.

Source: Naaman Abreu/Shutterstock

The peoples of the eastern forests supplemented hunting with the gathering of fruits, nuts, and vegetables. Many of these Eastern Woodland Indians were farmers, although agriculture was typically an adjunct to hunting and gathering rather than a mainstay. They lived in more or less permanent villages of houses constructed of wood or earth. Some built very large ceremonial structures. The tribes that became known to history as the “Mound Builders” piled earth and stones into pyramids, cones, and in one spectacular case in Ohio, the shape of a serpent more than one thousand feet long. Like the Plains Indians, the Eastern Woodlands tribes engaged in trade and warfare. They established alliances to secure territorial boundaries and limit the destructiveness of their wars. Some of these alliances were elaborate and long-lasting. The Iroquois, for example, formed a league or confederacy that persisted for centuries.

In what would become the American Southwest, the culture of the Pueblo Indians developed. The Pueblos built permanent villages of adobe and stone and practiced agriculture along rivers and streams from which they diverted water onto their fields. Like other Indians, they traded with their neighbors. Some of the Pueblos’ neighbors, including the Navajos, adopted such aspects of Pueblo culture as the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash. At Mesa Verde, in what would become southwestern Colorado, the Pueblo people known as the Anasazi constructed elaborate cliff dwellings that foreshadowed modern apartment houses.

TAOS PUEBLO The Taos Pueblo, still occupied today, is one of the best examples of Pueblo architecture.

Source: Jim Feliciano/Shutterstock

The Pacific Northwest was the home of yet another distinctive culture. The Chinook Indians and their neighbors exploited the bountiful resources of the region to become some of the wealthiest indigenous people in the Americas. They controlled the salmon fisheries of the Columbia River and its tributaries, catching the big fish by the tens of thousands as they migrated from the Pacific Ocean to their spawning grounds every year. The Chinooks lived in long houses built of cedar and held sumptuous feasts called potlatches, at which much of the point was to waste food in order to show off the hosts’ wealth. Indians from hundreds of miles away came to the Chinook fish camps to trade for dried fish, bringing with them products their own cultures had to offer.